We value your privacy

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

In our latest ‘Fundamentals’ explanatory guide, Hannah Cordwell takes a look at leaver provisions – breaking down the various categories of leaver and their consequences and typical negotiation points when a founder takes new investment.

When investors commit equity funding into early stage or growth companies, that funding is a direct vote of confidence in the founders.

In return, investors will want to ensure that those individuals are fully committed to growing the business and won’t exit stage-left the day after the funds are deployed but rather stay long enough to realise the business plan (and ideally, exit).

The equity documents (typically the articles of association) of a venture-backed business will therefore usually include detailed provisions aimed at both incentivising the founders to give their best and stay with the business, but also to act as a stick; to deter founders from leaving early or in circumstances that might be damaging to the value of the business, or else founders run the risk of losing their equity. Investors also want to make sure that if a founder does leave the business, sufficient equity will be freed up to attract a replacement manager without diluting the investors’ existing position.

The leaver provisions set out what happens to the founder’s shares if they cease to be an employee or director of the company. Typically, a founder should expect to lose at least a portion of their shares, unless they leave in limited circumstances that the investor has agreed are ‘good’. An important point to bear in mind is that typically the founder will own all of their shares at the outset – there are a few different mechanics used in order for the shares to be ‘lost’.

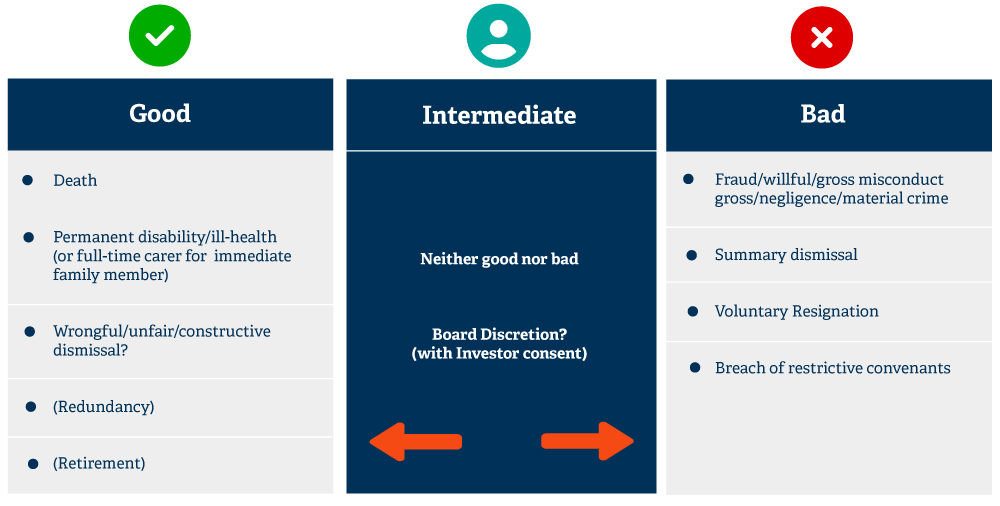

The consequences of leaving will depend on the circumstances surrounding the founder’s departure – clearly, if a founder commits fraud against the company, with the economic and reputational impact that may have, the investor will want to impose more severe consequences than in the unfortunate event that a founder becomes seriously ill. The graphic below shows the types of events one might see in a “founder friendly” outcome for the “Good”, “Bad” and, an in between category that is becoming more popular in VC transactions, “Intermediate” leaver definitions. A more “investor friendly” position will look very different.

As one would expect given the sensitivity and economic impact of a founder leaving, the specific wording of these definitions is usually hotly negotiated. In particular, we often spend time discussing the employment law terminology referred to in the graphic above – wrongful, unfair and constructive dismissal.

Wrongful dismissal is where the founder has been dismissed and such dismissal is in breach of their employment or service contract, typically where insufficient notice or payment in lieu of notice has been given. It is worth noting that this will always be in the company’s control, so it may be an easier give for an investor in the ‘Good Leaver’ category, as compared to unfair/constructive dismissal, particularly as the remedy would typically be damages equating to the value of the founder’s notice pay and benefits (which should have been paid in any case).

Contrast that position to unfair dismissal, which is a statutory claim for an employee with at least 2 years’ service. A dismissal will be unfair unless (i) the dismissal was for one of five potentially fair reasons and (ii) an employment tribunal finds that the dismissal was reasonable based on such reason. There are some reasons that are automatically unfair (for example, if the main reason for being dismissed is being pregnant) and in those circumstances, an employee does not need 2 years’ service to make the claim. A successful unfair dismissal claim would result in a maximum pay out of £105,707 or 1 years’ salary (if lower), but if the claim is combined with a successful discrimination claim, then the award can be increased. If an investor agrees to include unfair dismissal as a ‘Good Leaver’ event, they would typically look to limit it to non-procedural reasons and require the decision to be made by an employment tribunal or a court with no right of appeal.

Constructive dismissal can be said to have occurred when an employer breaks the fundamental terms of a contract of employment / service and, in response to that conduct, the employee has been forced to resign. Examples of such conduct include bullying or harassment. An employee who has been constructively dismissed will be entitled to damages for breach of contract, but if the dismissal is also unfair, then the employee may also be entitled to compensation for unfair dismissal.

Employment tribunals can be time-consuming and draining for management, so some investors may refuse to include unfair or constructive dismissal as ‘Good Leaver’ events due to a concern that the founder may be incentivised to bring a claim (noting that there are no fees to bring a claim in the employment tribunal, and employees will rarely be made to pay the employer’s costs, even if the claim is not successful).

As a final thought on leaver categories, in the BVCA’s model articles, ‘Bad Leaver’ is fairly narrowly defined – similar to the above graphic – and unless the leaving circumstances fall within that definition, the founder will be a ‘Good Leaver’. This means that the default position is ‘Good Leaver’, which is more founder friendly, so we often see investors attempting to move away from this.

There are broadly four different approaches taken in order to get equity back off a departing founder (and sometimes a combination of approaches).

1. Compulsory transfer

Upon ceasing to be an employee or director of the company, the founder (from then on, called a leaver) will be deemed to have given a transfer notice in respect of some or all of their shares (please see the “Reverse Vesting” section below). The articles will need to specify to whom those shares can then be transferred – to other shareholders on a pro rata basis, to an incoming manager or other existing managers, to an investor (although note that a VCT investor cannot purchase secondary shares) or perhaps to a warehousing vehicle or employee benefit trust. The decision as to the identity of the recipient of the leaver’s shares will likely be swayed by tax considerations (if the shares have value attributed to them at the point of transfer) and the practical consideration of whether anyone actually has the funds to purchase the shares.

2. Share buyback by the company

The leaver’s shares may be bought back by the company, either at nominal value or for a specified price. The statutory process under the Companies Act 2006 will need to be followed, so the ability for a company to buy back its own shares will be subject to shareholder approval and maintenance of capital rules. It is worth flagging that, for a company with EIS investors, EIS relief may be clawed back if there is a buyback in the three-year period following an EIS investment.

3. Automatic conversion into deferred shares

Some or all of the leaver’s shares, which are likely to be ordinary shares, are automatically converted into worthless deferred shares, which have no economic rights or voting rights. The deferred share class will be catered for in the articles and feature in the liquidation preference waterfall as receiving a nominal amount (e.g., £1 or £0.01) usually at the top level, so as to not inadvertently create a preference for VCT/EIS shares.

The benefit of using options 1-3 is that value is preserved for the remaining shareholders. In theory, the shares can be put into the hands of incoming management (subject to compliance with employment related securities rules) without further diluting the investors or other shareholders. However, in practice, if no-one is willing to pay the price or the tax consequences are too significant, then this may not always be possible.

4. Freeze the value

If there are no buyers for the leaver’s shares, the value of the leaver’s shares can be ‘frozen’ at the agreed market value of the shares as at their leaving date. The leaver would then retain their shares, holding them until an exit, but they don’t unduly benefit in any upside or growth in value of the company after their leaving date. It is not motivating for employees to be working hard and have someone no longer in the business benefitting from the upside

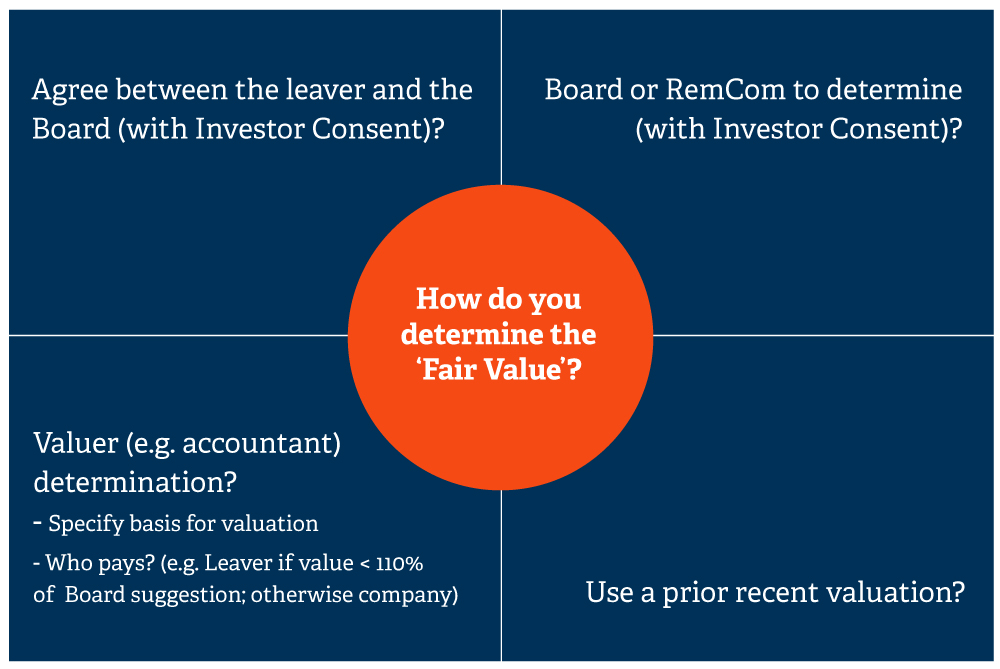

When using the transfer or buyback mechanics outlined above, careful thought must be given to the drafting as to how the shares will be priced. If the founder is a ‘Good Leaver’ then they will usually be entitled to ‘Fair Value’ for their shares (or at least their ‘vested shares’ – see below). Mid-way through a growth cycle, it can be tricky to determine what fair value is – the graphic below shows some of the ways we see this dealt with.

Adding to the complexity of the leaver provisions is the likely inclusion of vesting or, more accurately, reverse vesting. If this drafting is included, the outcomes for a founder leaving the business will improve over time, as the founder will become entitled to retain more shares as time passes by reference to a vesting schedule.

A typical vesting schedule is straight-line, on a monthly or annual basis, over a period of 3-4 years and calculated using a relatively straightforward formula. Vested shares will then be treated differently to unvested shares on a leaving event and will usually be allowed to be retained by the founder with full economic rights. Depending on the category of leaver, unvested shares are likely to be subject to the transfer / conversion mechanics mentioned above.

We commonly also see a vesting ‘cliff’ (for example for 1-year), whereby no equity vests within the 1st year of completion of the investment, such that if the founder were to leave within that 1st year, none of their shares would be vested. After the 1st anniversary has passed, 1 year’s worth of equity vests in one go, and then the rest of the vesting schedule would kick in. It is also common to see automatic or accelerated vesting on either a big-ticket investment round at a showstopping valuation or on an IPO.

If there are subsequent equity funding rounds in the company, it is likely that an incoming investor will look to re-set the clock on any existing vesting schedules, such that the founder’s shares reverse vest from the date of the new investor’s investment (and not the date of the previous investment, effectively ignoring any vesting that has taken place in the interim period). This can be a particularly sensitive point for founders, and a well-advised founder might push for at least a portion of their equity to be treated as vested, so that the clock is only re-set on any unvested shares at the date that the new investor subscribes for shares.

This article has covered the key points relating to founder leaver provisions, but there are lots of nuances and each investor will typically have their own house-stances on what can and cannot be accepted. One point worth bearing in mind is that there really isn’t such thing as ‘customary’ leaver provisions, so be wary of using that phrase in a term sheet unless the intention is to tackle leaver provisions further down the line during the negotiation of long-form documents. In tougher economic climates, provisions like these are increasingly put under the microscope, so we would recommend taking the time to ensure that the drafting is clear and unambiguous, and both founders and investors understand the position at the outset.

Hannah Cordwell

RW Blears

6 February 2024

EIS and VCT portfolio company mergers and reorganisations

Prev post

Changes to UK Corporate Governance Code 2024

Next post